Rocky road to reintegration

A look into the struggle of youth offenders after they

leave Singapore Boys’ Home.

Seeking shelter from the evening drizzle, 19-year-old Adam* cycled to a nearby mall. He steadied his food delivery bag and got off his bike.

The slim youth wiped the raindrops off his hoodie and removed it, revealing a tattoo of a creature, seemingly growling at anyone bold enough to stare at it. For now, it seemed to be snarling at a group of students, who had slowed down to look at him as they walked by.

Ignoring them, Adam silently checked his phone for food delivery orders. By then, he had already worked nine hours.

Instead of a new order, a message came in. His face lit up.

“My fiancée’s here,” he said. “I’m going to grab dinner with her.”

Adam rarely eats out, but that night was an exception. The next day, he was going to be charged in court for rioting.

Adam prepares to head home after a long day of work as a food delivery cyclist. He hoped to spend as much time as possible with his family before his court trial the next day, where the then 19-year-old would receive his eighth sentence.

Adam prepares to head home after a long day of work as a food delivery cyclist. He hoped to spend as much time as possible with his family before his court trial the next day, where the then 19-year-old would receive his eighth sentence.

Having been through several trials before, he compiled a mental checklist of everything he needed to get done before his day in court — like finishing his chores and transferring some money to his mother and pregnant fiancée.

Over the past six years, Adam has been to juvenile rehabilitation centre Singapore Boys’ Home seven times, and served another stint at the Reformative Training Centre (RTC) - a more secure facility that houses youths from 14 to 21 years old.

Adam’s reoffending streak might seem extreme to some, but he is not alone.

Ramping up integration efforts

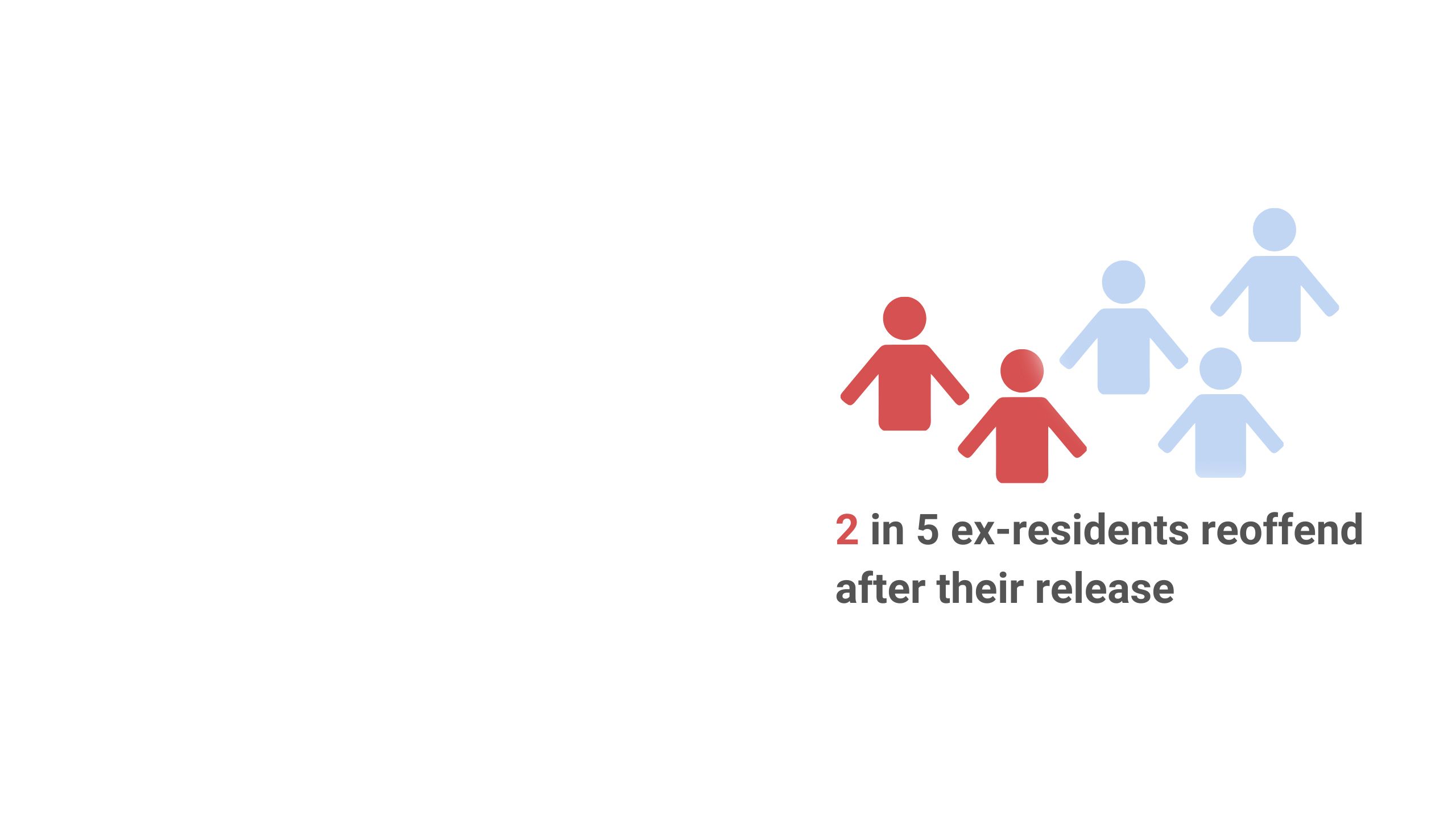

The reoffending rate for its youth homes residents hit an 8-year high last year, according to statistics from the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF).

MSF youth homes include the Singapore Boys Home and Singapore Girls Home.

Amongst former youth home residents released in 2014, two in five reoffended within three years of their release.

MSF also reviewed its reintegration plan for ex-residents last year. Most notably, the youths will get support for a longer period of time after their release to help them reintegrate better into society.

Post-care officers will remain connected with ex-residents for a full year, up from the original two months, allowing them to keep tabs on the youth and offer guidance when needed.

According to the ministry, the officer would help to strengthen the youths’ skills, connect them with community resources and support them in school and employment.

Beyond the four walls

Youth offenders charged in the Youth Court can expect a variety of outcomes. As far as possible, they are first considered for probation and rehabilitation instead of residential stays in a home, said the ministry.

The Boys’ Home and Girls’ Home are run by MSF and have much tighter security than other homes. They are manned by staff from the ministry and auxiliary police officers.

The controlled setting within juvenile institutions is very different from the conditions of the outside world, and many ex-residents find it difficult to adapt, according to Narasimman S/O Tivasiha Mani, Head of Rehabilitation & Reintegration Services in social service agency Trybe, which runs the Singapore Boys’ Hostel.

The Boys’ Hostel is a dedicated residence for youth offenders on probation. Mr Narasimman explained that the level of security in Boys' Hostel is lower than Boys’ Home, but the residents mostly face the same risk factors.

Trybe runs structured programmes dedicated to post-care, and Mr Narasimman himself works with boys towards the end of their stay to ensure they reintegrate successfully.

Old friends come knocking

Despite the post-care support Ben* received, he continued to reoffend after leaving Boys’ Home.

Ben, who is now 26, said that caseworkers from Boys’ Home tried their best to help him readjust by convincing his former secondary school to take him back in. But it did not change his mindset.

“Since the social worker put in so much effort, in front of them I wanted to make them happy. But actually I don’t feel anything (about school),” said Ben, who continued to mingle with the friends he made while at Boys’ Home.

Barely a month after his release, he went on a housebreaking spree with his previous Boys’ Home dormitory mates. They broke into 147 homes over two months. He was arrested and sent back to Boys’ Home, while his two older friends were sent to RTC.

Eventually, religion helped him turn his life around. Ben currently works as a mover and lives at The New Charis Mission, a Christian halfway house.

Post-care officers on the journey

Under the original post-care system, caseworkers in the Boys’ Home follow up with the youths for two months after they leave, through meet-ups and phone calls. They also link them to other support services in the community such as family service centres and school counsellors.

The frequency of their contact depends on the youths’ responsiveness, said Mr Ken Chelliah, Head of Therapeutic Casework Unit, under the Youth Residential Service (YRS). The YRS is a branch under MSF which oversees the Singapore Boys’ Home and Girls’ Home.

This system is set to change. For the first time, in September last year, MSF called for social service agencies to tender for post-care support services for ex-residents.

Instead of their caseworkers, a dedicated post-care officer will work with ex-residents like Ben for a year after their discharge.

“(They will) journey with youths in the community and link them to constructive sources of engagement such as school, employment or interest groups,” said an MSF spokesperson.

Post-care officers will start to engage the youths up to six months before their discharge to build trust and rapport. Hopefully, the new system gives them a longer runway to transition smoothly from youth homes into life outside.

The Salvation Army and REACH Community Services were awarded the tender in November 2019, and will reach out to the youths through house visits, phone calls, and conferences with schools or employers, according to information on the tender.

A pilot with 12 youths from the Boys’ and Girls’ Home is underway. This new support will be available for all ex-residents by end-2020, said Mr Chelliah.

Steps towards reintegration

In many ways, the reintegration process for current and former residents of Boys’ Home begins during their stay at the institution itself.

Boys’ Home operates on a strict and disciplined routine. It has youth guidance officers who watch over residents, and caseworkers who counsel and guide them. The youths also attend school or vocational courses while inside, to help them reintegrate smoothly when they are released.

But some boys have trouble keeping away from temptation after leaving Boys’ Home.

Adam wanted to stay crime-free so he could continue being his family’s sole breadwinner. But the food delivery cyclist, whose income supports his mother, fiancée and two younger siblings, said financial pressures took a toll on him.

Sometimes, when it got too stressful, he said he would knowingly break his curfew to be sent back to Boys’ Home. At times, he preferred being in Boys’ Home to being home, because his daily needs were provided for there, he said.

Even if they steer clear of their old ways, adjusting back to society’s norms is no easy feat.

“These boys go back into a world where mainstream definitions aren’t ingrained in them,” said Associate Professor James Patrick Williams, who studies youth cultures at Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

“If you go back to school and everyone knows you’ve spent a year in Singapore Boys' Home… you might get labelled and stigmatised. It might be difficult, and you might feel different and like an outsider,” he said.

This was the struggle Daniel* faced.

After eight years of life in institutions, including a children's home, Boys’ Town and Boys’ Home, Daniel decided to go back to school. But it felt like a different world to him.

"We're not used to anything. We don't even know what it is like to be a normal student," said Daniel, referring to himself and other ex-residents from Boys' Home.

“You only know you go to school have fun, fight, and do something stupid.”

Dealing with stereotypes and expectations was tough for Daniel, who was often called angkongsiao - a Hokkien term meaning ‘tattooed gangster’.

“When people say you are from a certain background and assume they know you - I hated that,” said Daniel, who is now in his 20s and currently serving his National Service.

Help along the way

Rebuilding their life may also be a lonely process. Family might be a source of support for most youths, but it is not the case for some youth offenders.

"Many such residents have poor adult role models, and lack family support," said Mr Chelliah, adding that the YRS works closely with residents and their families.

Jonathan*, 21, grew up with an abusive stepfather who was also involved in gangs. He was drawn into a fight and was sent to Boys’ Home for rioting.

In this void, there are other trusted adults stepping forward to guide these young men. They range from social workers, volunteer tutors and even strangers who offer their homes to ex-residents with no place to go.

Ex-resident Wilson Peh used to feel like all adults were authority figures.

He felt like his parents did not know him and were too judgmental of his friends, said Wilson, who is now 28 and a youth worker.

“(They said) ‘don’t be with these friends, they will only get you into trouble’, but it’s not all getting into trouble. There’s fun things I do with my friends too,” said Wilson.

In his wayward teenage days, he met a social worker who was determined to reach out to him. Too Seng Hong, who is seven years his senior, became the youth’s mentor and spurred him to turn over a new leaf.

Leaving their mark

Recent amendments to the law aim to make it easier for ex-residents of Boys’ Home to start anew.

Changes to the Children and Young Persons Act (CYPA), due to take effect in the second quarter of 2020, will protect the identities of juvenile offenders for life, making it illegal for them to be identified publicly unless they reoffend as adults. This is also why most of them are kept anonymous in this media report.

If asked, those who complete their Youth Court orders can also declare that they have neither been convicted before nor have a criminal record.

However, even without declaring their records as adult ex-offenders do, some ex-residents we spoke to said they still faced discrimination.

“After I started getting tattoos following my stints within Boys’ Home, I never got re-employed by the company I used to work at,” said Adam.

After four failed job applications, he decided to work full-time as a food delivery cyclist.

Thankfully, juvenile offenders are now given the chance to wipe the slate clean - literally. The MSF has partnered aesthetician Dr Kevin Chua in giving complimentary tattoo-removal services to Boys’ Home residents.

In 2017, Boys’ Home bought a tattoo removal machine of its own. Even after their release, eligible former residents are able to visit Dr Chua at his clinic to complete their tattoo removal sessions.

Former resident Jervin Tay, now 20, has also found a new way forward through brewing coffee.

In the last few months of his stay in Boys’ Home in 2018, his caseworker Ms Lim Li Min, helped him secure an intership with social enterprise Bettr Barista.

Work gave him a much-needed new direction.

“If (Ms Lim) didn’t plan all this, I come out I will 'blur', (and) not know what to do,” said the well-built youth, who is now serving National Service.

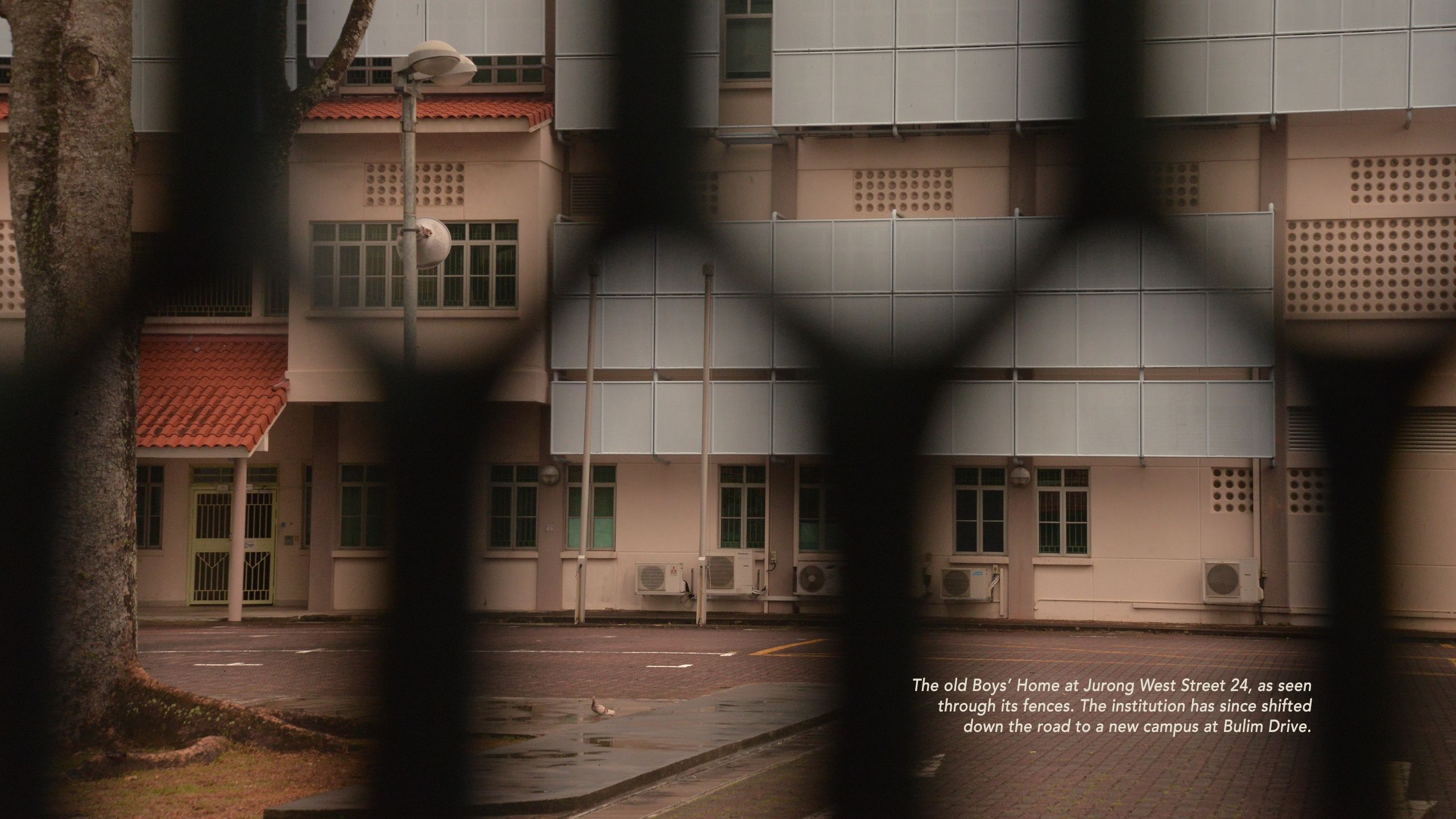

The changing face of Boys' Home

Besides extended aftercare, the physical space where these young offenders start their journey towards change has also gotten a facelift.

In November last year, Boys’ Home quietly traded its pastel blue-walled compound for a new building just down the road on Bulim Drive.

The high walls were replaced with a modest looking fence, and the old, peeling buildings with orange roofs are now cream and dark blue blocks. From afar, it looks like any other secondary school.

Residents now have access to facilities such as computer and science laboratories, and indoor spaces for learning, counselling and programmes, said Mr Chelliah, who oversees the Boys' Home.

Fighting for a future

A day after our interview with him, Adam fought hard in court. He hoped to get probation, but was sentenced to six months in RTC as he was a re-offender, said his social workers.

Since Adam went to RTC, his fiancée posted an ultrasound scan of her unborn child, along with photos of herself with Adam on social media platform Twitter.

Her captions reminisce their time together, and count down to the next time she can receive an e-letter from Adam again. Inmates in RTC can send their loved ones mail four times each month.

She is due to give birth in two months. Adam will not be around to witness it. In one of her tweets, she said her fiancé had asked to get a matching tattoo with her of their baby's name.

The youth wants to mark a new path in his future. When he leaves in August, he still has a long way to go.

*Names have been changed to protect their identities.